Slavery Reinterpretation Exhibition

Black New Englanders, both free and enslaved, were far more visible in the 18th century than many modern visitors to a town like Lexington might expect. The new exhibition and tour at Hancock-Clarke House aims to tell the stories of ALL the residents of the house, including Jack and Dinah, the enslaved Black servants of the Hancock family.

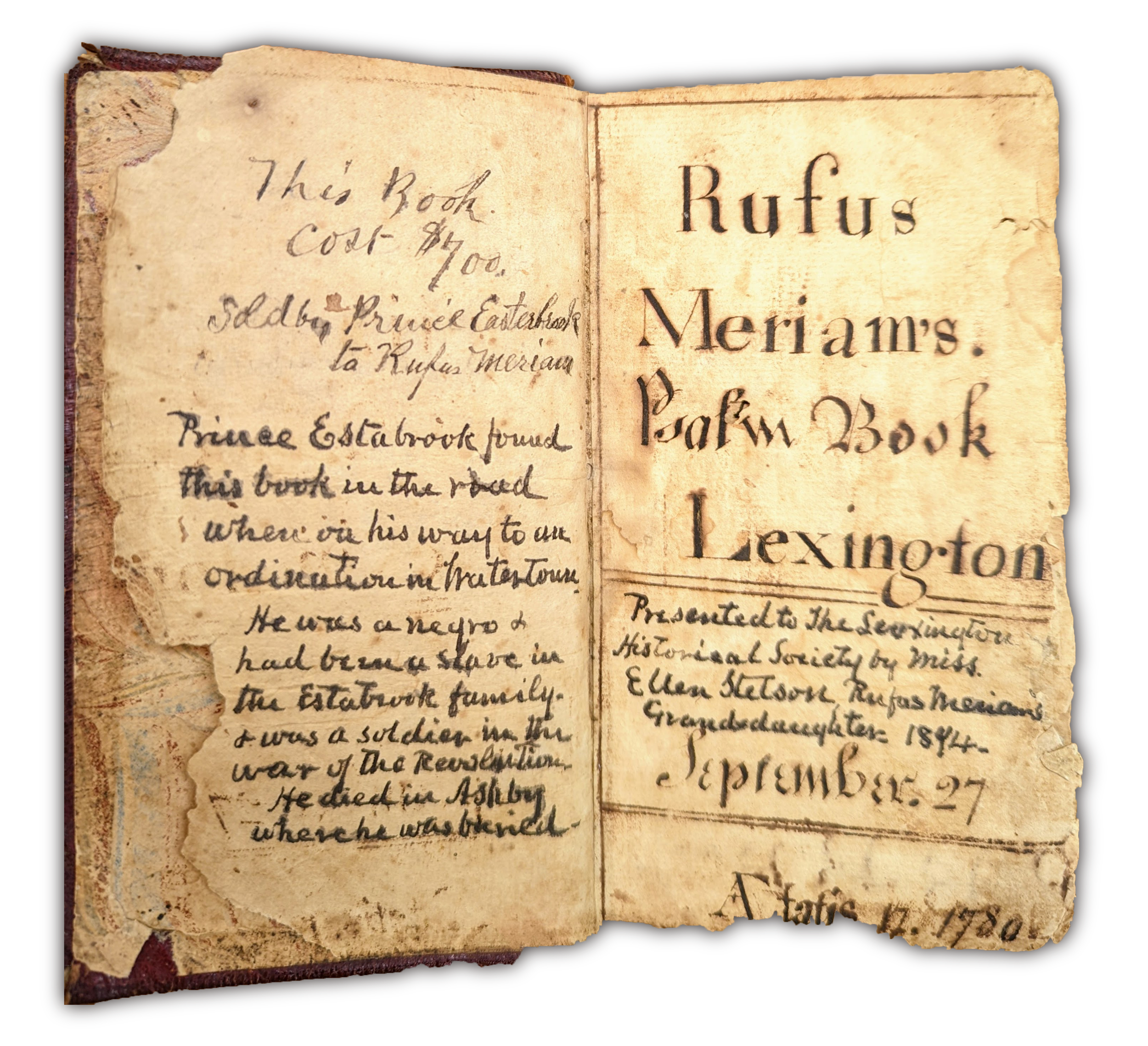

Left to Right: A New Version of the Psalms of David Fitted to the Tunes Used in Churches, 1765. On verso of fly-leaf: "Sold by Prince Estabrook to Rufus Meriam. Prince Estabrook found this book on the road when on his way to ordination in Watertown. He was a negro and had been a slave in the Estabrook family and was a soldier in the war of the Revolution. He died in Ashby where he is buried.” On April 19, 1775, Prince Estabrook joined the militia on the Battle Green and became the first Black soldier to fight in the Revolutionary War.

Receipt for the Lexington Militia Payroll in 1778 for Colonel Reed's Regiment in General Gates' Army. This receipt lists many Lexington names, including Eli Burdoo.

Letter from Edmund Munro to his wife written at Valley Forge, May 17, 1778. Edmund mentions the Lexington soldiers there are healthy and well, with the exception of Pompey Blackman (a Black soldier) and another. Blackman served in Colonel Gerrish’s regiment in April 1775, fought under General Arnold on Lake Champlain, returned home in 1777, then rejoined the fight in northern NY. He served a three-year enlistment in the 15th Massachusetts Regiment and was discharged in 1780.

This tax list (ledger) was committed to Nathan Munroe, the Lexington tax collector in 1800. The book contains names of town taxpayers, and the amount of state, town, poll, and county taxes collected from each of them in 1800. This page includes Prince Estabrook, the first Black soldier to fight in the Revolutionary War.

Liberty & Servitude

Black New Englanders, both free and enslaved, were far more visible in the eighteenth century than one might expect. This exhibition and tour aim to help us understand and appreciate the rich diversity that has characterized this town since the seventeenth century.

Freedom and servitude can be seen as two sides of the same coin. If you lived in Lexington in the eighteenth century, there were different types of servitude and freedom available to you, based on a variety of factors. The most restrictive was chattel slavery, which means the enslaved person was the legal property of another and was considered enslaved for life. Thousands of Black, indigenous, and mixed-race people were enslaved in this way, both in New England and other parts of the country.

Another type of servitude was term slavery, where an individual would be enslaved for a set period of time. For example, Lexington’s Margaret Tulip, a Black woman, was enslaved but should have been freed at the age of 22. As you will read in this exhibition, she had to file multiple lawsuits against the Muzzy family to permanently secure her freedom.

Indenture is a form of unfree labor under which a person pledges themselves against a loan or other debt. William Munroe, a White man and the ancestor of the family who owned Munroe Tavern, came to New England in 1652, probably as a prisoner of war from the Battle of Worcester during the English Civil War. William’s indenture was initially purchased by millwright John Adams of Menotomy; he later worked for Joseph Cooke of Cambridge before he absolved his debt and became a property holder in Lexington.

Lucy Clarke, a White woman, illustrates how being a woman limited individual freedom during this time. Lucy was the granddaughter of Reverend John and Elizabeth Hancock and the daughter of Reverend Nicholas and Lucy Bowes of Bedford. She married Reverend Jonas Clarke in 1757, and three years later, her brother Thomas sold this house to Jonas rather than Lucy, despite her lifelong connection to the house and land. As a married woman, she could not own property in her own name. Lucy also gave birth to thirteen children over a period of twenty-two years (1758-80), so the realities of childrearing meant that her time was decidedly not her own.

Poverty was another form of servitude in eighteenth-century Lexington. A group called the Overseers of the Poor ensured that residents of the town who had little means would have housing and some form of financial support. Lexington’s first “Poor House” was built in 1783 near what is now the Hayden Recreation Center on Lincoln Street. One of Margaret Tulip’s sons, Peter, moved back to town from Leominster around 1808 and would play the fiddle for dances at Munroe Tavern in the early nineteenth century. His daughters, Hepzebeth and Elizabeth, served as waitresses at these events. Despite having at least some paid work available, Peter, his wife Patty, and their daughters Vianna, Hepzebeth, and Elizabeth lived in poor houses in and around Lexington between 1808 and 1826.

Article VII of the Massachusetts Constitution begins, “Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men.” Reverend Clarke represented Lexington at the Constitutional Convention for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts from September 1, 1779, until June 16, 1780. The Massachusetts Constitution served as a model for the United States Constitution. As Clarke and his fellow community leaders codified important concepts like this for posterity, do you think they considered how ideals of freedom, liberty, and independence might be applied to all classes of people, in the eighteenth century and into the future?

Bill of sale of a man named Pompey, conveyed from Ruth Bowman, widow, to William Reed, both of Lexington, for the sum of fifty three pounds, six shillings, eight pence. June 5, 1752.

As mentioned previously, Reverend Clarke’s leadership and ideas meant this house was the site of frequent discussion among patriot leaders in Massachusetts. As you explore the house with your guide, you’ll learn more about the people who lived, worked, dreamed, and died in this house. What did freedom look like for John Hancock? Lucy Clarke? What did it look like for Dinah?

-

Lucy Clarke

Lucy Clarke, a White woman, illustrates how being a woman limited individual freedom during this time. Lucy was the granddaughter of Reverend John and Elizabeth Hancock and the daughter of Reverend Nicholas and Lucy Bowes of Bedford. She married Reverend Jonas Clarke in 1757, and three years later, her brother Thomas sold this house to Jonas rather than Lucy, despite her lifelong connection to the property. As a married woman, she could not own property in her own name. Lucy also gave birth to thirteen children over a period of twenty-two years (1758-80), so the realities of childrearing meant that her time was decidedly not her own.

-

William Munroe

William Munroe, a White man, and ancestor of Munroe Tavern’s owners, came to New England in 1652 as a Scottish prisoner of war from the English Civil War. William’s indenture was initially purchased by John Adams of Menotomy; he later worked for Joseph Cooke of Cambridge before absolving his debt and becoming a property holder in Lexington.

In This House

This house was the parsonage (home of the minister) for the town of Lexington during much of the eighteenth century. Reverend John Hancock and his wife Elizabeth moved to Lexington in the late 1690s and built their first home on the property around 1700. By the 1730s, the Hancock’s had a 50-acre property, containing one mansion house and one barn.

Dendrochronology (the science of dating events and environmental change by using characteristic patterns of annual growth rings in timber) indicates that the beams for both parts of the house are from trees cut mostly in the winter of 1736-1737. Usually timber would have been used while green or unseasoned so we know that construction of the current Hancock-Clarke House would have occurred in 1737 or 1738. Jack, an enslaved person living with the Hancock family beginning in 1728, may have contributed in some way to building this house.

The rural setting of Lexington at the time and the necessities of life in colonial New England required a significant amount of labor. The Hancocks’ enslaved servants, Jack and Dinah, would have performed some of the wide range of tasks needed to run an eighteenth century household. Jack was likely responsible for many of the Hancocks’ domestic chores: farming, tending animals, preparing food, chopping wood, and transporting goods. Dinah may have helped with firetending, cooking, sewing, dairying, childcare, and more.

The Hancock or Clarke House, Lexington. Circa 1878. Hand colored by John B. Dodge.

In 1760 after the deaths of John and Elizabeth Hancock, their son Thomas, a Boston merchant, sold the property, which then contained a “mansion house, barn and edifices thereon” to Reverend Jonas Clarke, the new minister of Lexington as of 1755.

Because of Reverend Clarke’s leadership and revolutionary ideas, the Hancock-Clarke House was the site of frequent consultations among patriot leaders in Massachusetts, such as John Hancock (grandson of Reverend Hancock), Samuel Adams, and others.

In April 1775, John Hancock and Samuel Adams stayed at this house while attending the Provincial Congress in Concord. Around midnight on April 18, Paul Revere and William Dawes rode to this house to warn Hancock and Adams of the approach of British Regulars.

The historical record tells us what happened next - British troops marched into Lexington and fired on the local militia, a day-long battle was joined between local militias and government troops, and by the end of the day, open war with Great Britain seemed inevitable.

As a community and religious leader with nine children at the time of the Battle of Lexington, Reverend Clarke could contribute more to the cause with his pen than with his sword. The documents that he wrote and the ideas about freedom and liberty that were discussed in this house helped light the fires that eventually led to American independence.

The first page of a printed draft of the Constitution of Massachusetts with handwritten annotations and edits by Jonas Clarke. Clarke represented Lexington at the Constitutional Convention for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Many of these annotations written in Clarke's hand can be seen in the final draft of the Constitution that exists through the present day.

Original watercolor of the exterior of Hancock-Clarke and of the elm tree that stood in the front yard. Painted by Beatrice Tolman Sawyer and presented to Lexington Historical Society in 1900. The elm tree was planted in 1701 by Reverend Hancock.

Map, "Plan of the Town of Lexington in the County of Middlesex, From a Survey made by John G. Hales in August 1830. Pendleton's Lithog. Boston."

Black Residents of Lexington

There were at least one hundred sixty people of African descent who were Lexington residents from the end of the seventeenth century to the beginning of the nineteenth century. Their lives help us reflect on the humanity acknowledged or withheld in eighteenth century New England, depending on circumstances or the color of skin.

Ann & Phillip Burdoo

Ann and Phillip Burdoo arrived in Lexington as free people. Ann was baptized into the Lexington church by Reverend John Hancock in 1708. Their children - Phillip, Eunice, Moses, Aaron, Phineas, and Lois - were all baptized by 1729. Ann and Phillip lived on Bedford Road across from Simonds Tavern. They owned land, as did other family members. In 1714, Phillip was fined, along with seven white men, for enclosing certain public highways within their lots. Phillip, Moses, Aaron, and Eli (Philip and Ann's grandson) Burdoo all paid taxes in the 1770s. Two of Ann and Philip’s grandsons, Eli and Silas, fought in the Revolutionary War. Later, Silas moved to Vermont where he prospered. Ann and Phillip’s great-grandson, also named Silas, fought in the famed 54th Massachusetts Regiment in the Civil War.

Cate & Prince Chessor

Cate was born in 1741 in Boston. Phineas Taylor of Boxborough bought her as a toddler for a box of butter. She gained her freedom in 1772 and married Prince Chessor of Lexington. Their two children who were born in Lexington, Ruth and Lucy, were both baptized by Reverend Jonas Clarke. Reverend Clarke occasionally hired Prince to do the skilled and difficult work of preparing flax for spinning, and Cate, the equally skilled work of spinning the flax into linen thread. By 1777, Cate, Prince, and family were living in Boxborough in a house that Phineas Taylor had given to them. They had 5 more children – Molley, Eunice, Prince James, and twins Paul and Silas - all of whom were baptized. Cate died in 1790 of spotted fever, having caught it while nursing Phineas Taylor. Her descendants lived in Boxborough, where they owned land and prospered.

Venus Roe

Venus Roe was an enslaved child born about 1744 in Lexington, probably into the Munroe family. At about age three, she was taken from her mother and given to Swithin Reed of Burlington. Venus was in the home of James Reed (Swithin’s son) when he opened his house to John Hancock and Samuel Adams as they fled Lexington on April 18-19, 1775. After slavery effectively ended in Massachusetts in the late 1700s, Venus returned to Lexington for a time. During her bondage, Venus was not given the opportunity to learn a trade. With no specialized skills, she could not support herself and returned to the Reeds, whom she served for the rest of her life. She died at age 100, having spent a century in servitude.

Kate & Quawk Barbados

Kate and Quawk Barbados joined the Lexington church as a married couple in July 1754. In November 1755, their children, Isaac and Mary, were also baptized in the First Parish Church. By July 1756, when their son Abel was baptized, Quawk and Kate had acquired their freedom and taken the surname Barbados. Quawk Barbados died May 5, 1757. Isaac, their eldest child, was killed fighting in the Revolutionary War. Their youngest son, Abel, moved to Boston. By 1796, he had married, raised a family, and bought the land. He is buried in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground.

Margaret Tulip

Margaret Tulip pursued her own liberty by filing a lawsuit against William Muzzy of Lexington, who kidnapped her and pronounced her a slave, though her term of enslavement had legally ended when she turned 22 years old. Margaret was represented by Jonathan Sewall, Massachusetts attorney general, and one of Muzzy’s lawyers was future president John Adams. Margaret was successful. Her legal status as “a free woman and not a slave” was conclusively recognized when her Freedom Suit was resolved in 1770. Margaret’s story is unique to her and representative of Black women in eighteenth-century Lexington, whose freedom and liberty were violated by people and institutions who perpetuated slavery.

Peter Tulip and Family

One of Margaret Tulip’s sons, Peter, moved back from Leominster around 1808 and would play the fiddle at Munroe Tavern dances in the early nineteenth century. Two of his daughters served as waitresses at these events. Despite having paid work available, Peter, his wife Patty, and their daughters Vianna, Hepzebeth, and Elizabeth lived in poor houses in and around Lexington between 1808 and 1826.

Deed from Isaac Powers to John Hancock for Jack, April 22, 1728. Hancock family papers, 1728-1815. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Jack

Jack was called a “boy” when he was purchased by Reverend John Hancock from Isaac Powers of Littleton in 1728. However, Jack may have been a teenager at the time of his purchase, as the price Hancock paid, £85, is consistent with the sale of other teenage enslaved people of the time. The money was provided by the town of Lexington so that their minister could focus more on his religious duties and less on domestic labor.

Unlike the white members of the household, whose lives were fully recorded, Jack’s life is not well illustrated in the documentary record. It is unknown where he was born, who his parents and potential siblings were, how old he was when he was enslaved, whether he married, or how long he lived.

“To Beef and Mutton sent by Jack £5.9.9”: this note appears in an account between Reverend Hancock and his son Thomas, a merchant in Boston. Whether it refers to the same Jack is unknown, but it demonstrates one type of work carried out by enslaved people in New England. They might cart goods or drive livestock, work for a shopkeeper or craftsman, be hired out as day labor, or perform house or field tasks.

Jack was likely responsible for many of the Hancocks’ domestic chores: farming, tending animals, preparing food, chopping wood, and carrying goods between Hancock households. The artifacts of household work displayed in this room speak to Jack’s life. The luxury goods in the house illustrate what his labor helped buy. The Hancocks’ wealth was, at least in part, a result of Jack’s labor.

Dinah

When Dinah became enslaved in the household of Reverend John and Elizabeth Hancock is unknown. The first mention of her in family records states that a dress was purchased for her to wear at Reverend John Hancock’s funeral in 1752.

Reverend Jonas Clarke and his wife Lucy, the Hancocks' granddaughter, lived in the parsonage with Elizabeth Hancock after Reverend Hancock's death. Reverend Clarke baptized Dinah on September 9, 1759. Elizabeth, who died in 1760, freed Dinah in her will.

Reverend Clarke took responsibility for Dinah, which was required by the town of Lexington, and the Hancock and Clarke families paid for Dinah’s board with other members of the family. By 1775, when Dinah may have moved to Elizabeth (Hancock) Bowman's house in Dorchester, Jonas and Lucy had nine children. If Dinah lived with the Clarkes at any time during the 1760s, it is reasonable to assume that she may have helped with childcare.

It is not believed that Dinah was in this house when the events of April 19, 1775 took place. John Hancock, who also assumed some financial responsibility for Dinah following the death of his grandmother, was asked to provide compensation to the Bowmans for six hundred twenty-three weeks of boarding for Dinah from March 30, 1775 to March 30, 1787. It is unclear why the boarding arrangement ends when it does. Perhaps Dinah had died by 1787, or perhaps she had left the Bowman home. It is clear, however, that Dinah spent much of her life deeply intertwined with the Hancock and Clarke families.

Funding for this exhibition was provided by the Community Endowment of Lexington, an endowed fund of the Foundation for MetroWest.

This exhibition was supported by the research of many dedicated local historians and community members. A substantial amount of new research was produced specifically for this exhibition by Dr. Robert Bellinger of Lexington.

Lexington Historical Society Exhibition Curator: Stacey Fraser; Exhibition Designer: Nicole DeCicco; Executive Director: Carol Ward.

Other contributors to this exhibition were Leslie Masson and Margaret Micholet. Research on Black citizens of Lexington was provided by the above, as well as Beverly Donhan, Anne Grady, Richard Kollen, Andrew Lucibella, Sean Osborne, George Quintal, and members of Lexington Historical Society's Slavery Advisory Board and the Association of Black Citizens of Lexington.